What is Managed Grazing?

Managed grazing involves carefully controlling livestock density, and the timing and intensity of grazing. Compared with conventional pasture practices, it can improve the health of grassland soils, sequestering carbon.

Grazing management is the care and use of range and pasture to obtain the highest yield of animal products while supporting forage plants, soil, water and other important land attributes. [1]

Three managed-grazing techniques that improve soil health, carbon sequestration, water retention, and forage productivity include [2]:

- Improved continuous grazing adjusts standard grazing practices and decreases the number of animals per acre.

- Rotational grazing moves livestock to fresh paddocks or pastures, allowing those already grazed to recover.

- Adaptive multi-paddock grazing shifts animals through smaller paddocks in quick succession, after which the land is given time to recover.

Improved grazing can be very good for the land and sequester from 0.5 to 3 metric tons of carbon per acre. However, it does not address the methane emissions generated by ruminants (cattle, sheep, goats, etc.), which ferment cellulose in their digestive systems and break it down with methane-emitting microbes. [3]

Solution Applications in Alberta

Extensive areas (about 10 million acres) of both native and agronomic grazing exist in Alberta. About half of this land, including much of the native pasture, is public land and is managed by Alberta Public Lands.

Nearly all Alberta pastures currently producing beef or dairy products use Technique 1 as listed above. The second technique, Rotational Grazing, is in wide use in the larger ranches. However, Adaptive Multi-Paddock Grazing is still controversial in the larger ranches. The fencing it requires would be very detrimental to wildlife which co-exists on native grassland. However, this approach may be appropriate for smaller cattle operations in the parkland region. [4]

Reducing Emissions

Carefully managed grazing leads to healthier soil that has a greater amount of organic carbon. As soil health increases, both productivity and grazing capacity increase while maintaining biodiversity.

To understand how managed grazing works, it must be understood that all plants maintain a balance between the amount of above-ground tissue (shoots) and the below-ground tissue (roots). When the leaves and stems are removed, a proportional amount of “root” will die to maintain the balance. The dead root gradually decays, releasing the carbon over a period of decades. The plant re-grows new shoots and roots over a few weeks, using carbon from the air. Grazing will steadily pump carbon into the soil with this process.

Because grasslands store their carbon in the ground, they are very resistant to fires. In contrast, forests can empty their carbon reservoir in minutes.

The growth potential of forage plants on range and pasture is determined by:

- plant species

- previous grazing management

- leaf area

- day length

- temperature

- availability of water

- availability of soil nutrients

Grass fires may have led to a significant amount of carbon being fixed through a natural biochar process. [5]

However, extensive grazing accounts for only a small part of the total cattle production in Alberta. Virtually all cattle spend months in feedlots before slaughter. In these facilities, excess feed leads to increased methane production, while poor manure management also generates large quantities of methane. Beyond this, the farms which produce the feed grain are, in themselves, sources of enormous amounts of greenhouse gases. An increased emphasis on consuming grass-fed beef would help reduce the overall GHG production.

Application Status in Alberta

Ranchers with extensive native pastures generally manage them to preserve range health, which also sequesters carbon in the soil.

Landowners with smaller parcels of land and fewer cattle often self-identify as farmers. These may be cow-calf operations which generally raise their own forage and other feed, and have higher profit per animal. The farm may include grain or other crops, with the grazing being only part of the process. Increasingly, off-farm income provides significant support for the farm. In any case, these operations generally have tame pasture using agronomic species. Not being range management specialists, their lands are often not managed to build soil carbon.

Emission Reduction Potential (MtCO2e)

In progress.

Economic Impact (Cost per MtCO2e)

In theory, better management of grazing leads to greater financial returns: it brings a profit!

Better range health allows more cattle to graze on a given pasture, while ensuring better resilience in the case of drought or other climatic extremes. Marketing beef as “grass fed” enables ranchers to access the more exclusive markets and receive higher returns.

On the other hand, ranchers may not be interested in, or skilled at, doing the marketing and promotion required for this approach.

Life Cycle Emissions

Even though cattle grazing leads to increased soil carbon, they also belch out methane during the process. The relative amount of each varies with the situation.

Agrologists are researching how to minimize the methane production. For example, high-nutrition feed such as in feedlots leads to higher methane production, while grazing on native pasture (grass-fed) has much lower methane production. Cattle that have been raised on the open range become climate liabilities when they move to a feedlot.

Co-Benefits

Co-operation among farmers can have benefits by sharing resources, including equipment and labour.

Maintaining native grassland for cattle grazing also provides habitat for dozens of species at risk. Without the economic return of cattle, considerable land would be cultivated and used for cereal crops.

Jobs and Training

Ranchers do not have time, education or interest to take advantage of the latest research. There is room for consultants to provide management expertise. Several companies provide this service to some extent.

District Agriculturalists used to provide this service, but these positions have been eliminated by the Alberta.

Field Days are also well attended, and are appreciated for both the social and educational opportunities. Ranchers are seen as more attuned to the environment as compared to farmers.

Partnerships & Organizations Working on Solution

One third of Alberta’s pasture is owned in relatively small parcels of less than 5 square miles. These people would benefit from more expertise.

Conservation groups put conservation easements on land valuable to wildlife such as Nature Conservancy of Canada, Alberta Conservation Association, and Ducks Unlimited.

Alberta beef producers may be dominated by small-time farmers.

4-H Clubs are groups that provide up-to-date information to future farmers. The information may stress agrichemical approaches, but this curriculum might be changed with discussions at the provincial level.

Indigenous Involvement

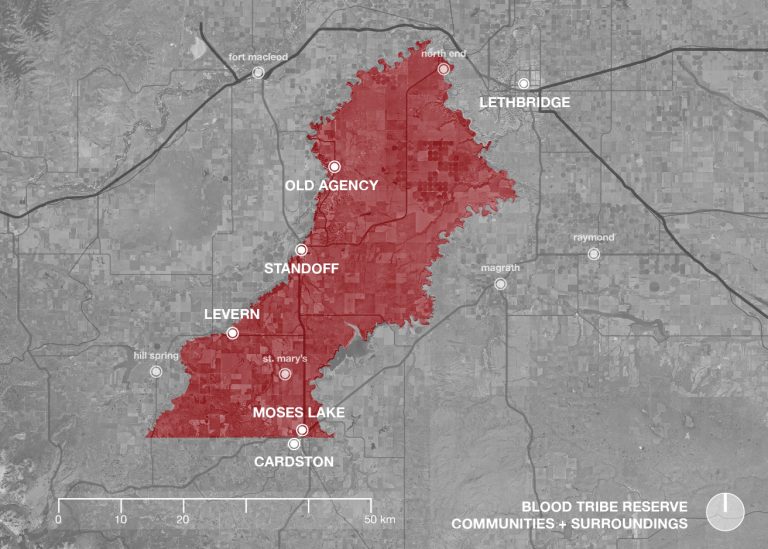

The Blackfoot people in southern Alberta have three large reserves. All of these participate in the Iinnii Initiative which promotes the re-establishment of bison on native grassland. The return of this cultural icon and ecological keystone species would have far-reaching benefits for cultural identity, wildlife conservation and ecotourism. The Blackfeet Reservation in Montana already has a herd of hundreds of bison.

Ranching would be more in tune with the historic aboriginal lifestyle. However, considerable parts of these reserves are leased to white farmers, leaving less land for ranching.

(Source: Blackfeet Nation)

Regulatory Status in Alberta

A grazing lease is a formal disposition from the Government of Alberta, normally granted on public land where grazing is considered to be the best long-term use of the land. About 8 million acres (3.3 million hectares) of Crown grazing land is used by livestock producers under various dispositions. Today, about 5,700 grazing leases cover an estimated 5.2 million acres (2.1 million hectares). Leaseholders have exclusive right to the use of land for grazing purposes. Public access to lands under a grazing lease is governed by the Recreational Access Regulation under the Public Lands Act.

The Government of Alberta is responsible for the management of natural resources but the Government of Canada has final authority for wildlife, and can both support and require conservation efforts. This has happened recently in support of the Greater Sage-Grouse, a critically endangered bird. The federal government provides incentives for some beneficial ranching practices in Saskatchewan while also requiring some actions in Alberta.

Further Implementation

- Education for farmers from farm operations of all sizes to be able to access more information about effective grazing management practices and how to implement sustainable grazing management plans

- Subsidy for soil assessment studies that can be accessed by farms (large and small) (look into programs that already exist through major fertilizer companies)

- The provincial government has laid out objectives along with performance measures in a Grazing Lease Stewardship Code of Practice for leaseholders but this should be assessed and amended to ensure the inclusion of lower-carbon practices

- Social Changes – educate people about “recreational agriculture”, particularly the severe overgrazing due to horses

Get Involved

For individuals:

- Look for “grass fed” beef in supermarkets.

- Buy meat directly from ranchers at farmers markets.

- Avoid buying meat, especially processed meat from American companies. This product generally comes from factory farms.

For ranchers:

- Seek advice from conservation organizations such as MULTISAR, Cows and Fish, and Alberta Conservation Association.

- Consider forming partnerships with marketing specialists to receive greater returns from grass-fed beef.

Overall Solution Priority for Drawdown Alberta

High

Sources

- Beneficial Management Practices: Environmental Manual for Alberta Cow/Calf Producers (↩)

- Potential of Rangelands to Sequester Carbon in Alberta – Report Summary (↩)

- Project Drawdown (↩)

- https://www.alberta.ca/range-health.aspx (↩)

- Dynamics of Fire and Grazing By Bison On Grasslands In Central Alberta by R. Grace Morgan & R.J. Hudson (↩)